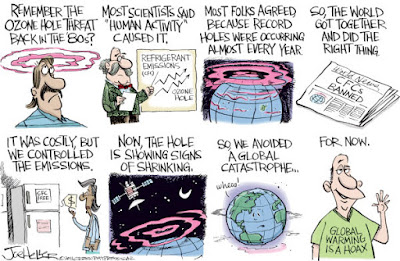

‘Bringing down emissions of greenhouse gases asks a good deal of

people, not least that they accept the science of climate change’

Illustrating that ‘barriers to mitigation action lie,

primarily… within the domestic sphere’, Green

(2015) emphasises the importance of convincing wider society that decarbonising

the global economy is in their “self-interest”, and challenges ‘traditional

assumptions’ that focus on the costs generated by climate mitigation action.

As a society driven by money and consumerism, with any

mention of disruption to our habitual lives and what Green calls “the size of

the economic pie”, panic strikes.

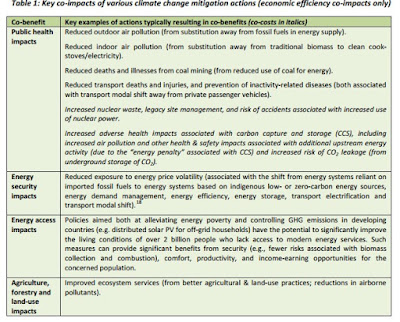

In response, Green defines a Nationally net-beneficial mitigation action, proposing

a framework which simultaneously increases economic efficiency and reduces

greenhouse gas emissions. Encouraging us to consider “national interests” which

stretch beyond economic efficiency, Green draws our attention to

‘overwhelmingly positive’ direct and co-impact benefits in ‘social welfare,

individual well-being, social justice, sustainable development, environmental

conservation and responsible global citizenship’.

Table 1) Key co-impacts of climate

change mitigation actions (Green,

2012)

So perhaps now we have a framework which speaks to state and

society alike? After all why do anything if it’s not going to benefit you,

right? (I’m being sarcastic.)

However, although entertaining and exploiting

the economic appeal of the world’s wealthier societies to stimulate their

contribution to climate mitigation, I think it’s disgraceful that it should

require this much persuasion and effort.

In

a special

climate change report ‘Hot and Bothered’,

The Economist (2015) dedicates a section to countries most affected by climate

change, highlighting their efforts to mitigate change through ‘conservative

adaptation’, and I think putting the world’s richest nations to shame.

Take a look at Bangladesh, TheEconomist (2015) stated that ‘very few countries of any size are more gravely

threatened by climate change than Bangladesh’. Battered by multi-dimensional

climatic events including drought, flooding, cyclone activity, rising

temperatures and sea level rise, Bangladesh faces the ‘most spectacular threat

to human life’.

This nation’s entire livelihoods are at stake, but are they sitting

by, worrying about economic costs?

No.

With

the help of BRAC, a large NGO, farmers are being trained to ‘switch from

ordinary rice to salt-tolerant varieties, or to grow sunflowers instead’ (The

Economist, 2015). BRAC

have also pioneered a combination of agriculture and aquaculture due to the

flooding of fields by freshwater during the monsoon season. This has provided

the farmers with an alternative trade, enabling them to ‘raise freshwater fish

in their flooded fields’ yet simultaneously grow rice ‘as the ground dries out

[and] the fish move to a pool at one end’. This ‘integrated rice-fish farming’

provides Bangladesh with both socio-economic and environmental benefits – for

more information on this look at Ahmed

and Garnett’s paper (2011).

|

| Integrated rice-fish farming Bangladesh |

Innovations such as these are spreading throughout LEDCs,

reflecting their need and accepted responsibility to adapt to changing

conditions. Although they may not have the economic means to effectively

mitigate such changes, their proactive nature speaks volumes. Begging the

question “Why aren’t the rich nations doing anything?”.

As Green (2015) puts it rather nicely, ‘domestic barriers retard

the pursuit of national net benefits from mitigation action’ - unwilling to

change lifestyles and too lazy to look beyond short-term losses.

Wake up society. Smell the… pollution?... and realise that

we have the power to be greater if we help mitigate climate change.

I will end with a quote from Green’s

(2015) influential paper and leave you with something to go away and really

think about:

‘If the majority of

mitigation action can be done in ways that are nationally net-beneficial, then

one might well ask: why do we not see mitigation action commensurate with the

scale of nationally net-beneficial action that is available? To borrow a

phrase, why are we waiting?’